Barrel making has been around for 2,000 years. But chances are, you’ve never met a cooper.

So let’s take care of that now. We’d like to introduce you to Nate, the cooper at Rolling Thunder Barrel Works in Newport, Oregon.

In 2015, Rogue acquired vintage French WWII-era coopering equipment and built Rolling Thunder Barrel Works. Longtime employee Nate Linquist was tapped to be Rogue’s first cooper and spent a year and a half apprenticing, learning the ancient art of barrel making.

Using Oregon Oak, Nate assembles, raises, toasts, chars, hoops, heads, hoops again, cauterizes, sands and brands each barrel, one at a time, all by hand. At full capacity, he makes one barrel a day.

How Barrels Are Made

Making the Staves

Nate first assembles the staves, which are funny shaped pieces of wood. Curved on the inside, rounded on the outside, beveled on the edges, wider in the middle than on the ends. No two are exactly the same. Put them all together and you get the outsides of a barrel.

How does a straight piece of wood become a stave? It isn’t easy.

The wood is cut four ways. Planers hollow out the insides and round the outsides. Jointers bevel the edges and give the wood a wedge like shape. This equipment is extremely rare, dating back to pre-WWII France. You can’t get replacement parts for them at Home Depot.

The third piece of gear is a radial arm saw that cuts all the staves to the same length. It’s not rare, but it’s still important.

Assembling the Staves

Nate clamps the completed staves to a hoop and begins arranging them in a circle. As we mentioned earlier, no two staves are exactly alike. So no two Rolling Thunder Barrels are alike either. When he’s got the puzzle figured out, Nate numbers the staves so he knows how to reassemble the barrel later – just in case. This is a trick dating back to the Roman Empire era.

He pounds two hoops over one end of the barrel. The other side is open and flares out like a skirt. So guess what we call it?

Toasting & Blending

Nate starts fires in small metal buckets that are also known as cressets. The secret to coopering is heat. Heat is what makes our tough as nails Oregon Oak easier to bend and shape.

The fire then toasts the insides of the barrel to caramelize the sugars in the wood. It’s a lot like toasting a marshmallow. Eating a plain one is sweet, but a toasted marshmallow tastes even better.

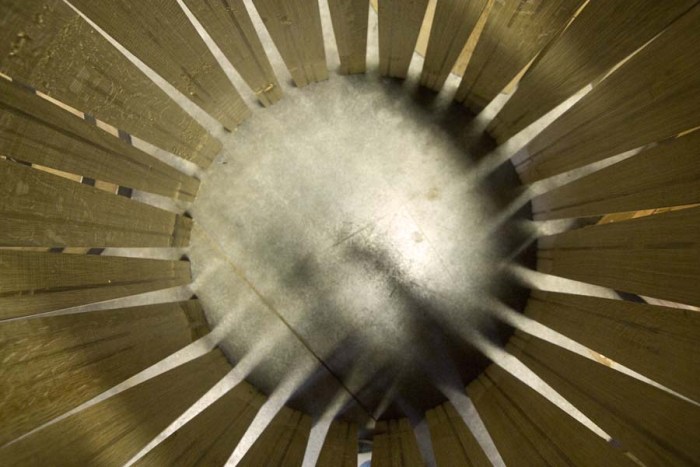

Meanwhile, as the barrels toast, hydraulic rings push the open ends of the skirts together until you get something that looks like this.

Toasting is critical because how you toast releases different flavors from the wood. A light toast highlights fresh oak flavors. A medium toast creates vanilla, caramel and bread notes. Medium Plus toasting brings out cinnamon, nutmeg and coffee flavors. Any or all of these flavors will infuse themselves into whiskey and other spirits during the aging process.

Charring

This is one of the most dramatic moments in coopering. Nate will literally set the inside of the barrel on fire and wait for about 45 seconds, or until his nose tells him he’s reached the right level of char.

Then he extinguishes the fire with water and a lid to dampen the flames. Charring leaves a layer of pure carbon that filters the spirits and gives it color. It will also add smoky flavors.

Since we make our own barrels, Nate can create any level of toast and char we want, and customize it to the spirit or beer we will age in the barrel.

Hooping

While the barrels are still smoldering, Nate slips temporary hoops over the ends. Hammering them into place with a cooper’s hammer and a driving iron. But he’s not done yet. He and the barrel are off to the hoop press which completes the job of pushing the hoops into place.

A barrel will be hooped at least twice. The first time with temporary hoops to finalize the bending and shaping. Then another time with brand new hoops so that it looks pretty.

But how do you cap both ends of the barrel so that it holds water, beer, spirits or any other liquid?

Wooden buckets, with a cap on one end, are 5,000 years old. But they leaked and were only good for carrying grain and other dry goods. It wasn’t until 350BC that the Celts of Central Europe figured it out. Humans were coming out of the Iron Age and finally had tools that were sharp enough and precise enough to make this one all-important cut.

That groove you see inside the barrel was the technological breakthrough we’d been waiting for. Today we call it a croze. The croze allows the cooper to loosen one end of the barrel, slip in a round piece of wood called the head, and tighten everything back together. Do this on both ends and you’ve got a barrel. Precision is critical. The head and the croze must fit perfectly or the barrel will leak.

The Crozer

The tool that makes this crucial cut is called a crozer. Trust us, you’ve never seen anything like it. One end holds the barrel in place, while the other end has monster-sized spinning blades that make the cuts.

The Heads

We make our heads with the same wood we use to make the staves, Oregon White Oak harvested from the Coast Range, about an hour’s drive from Rolling Thunder Barrel Works.

Nate cuts a groove one side of the planks, then a tongue on the other side. They fit together tongue and groove style like flooring. Then he cuts them into circles with a band saw.

But the round pieces you see above are too crude to fit into the croze. The edges must be trimmed and beveled so they fit as accurately as possible. Nate makes that cut with the rounding saw. When he’s satisfied, he slips the heads into the croze and tightens both ends with the hoop press.

The Bunghole

In coopering, the bunghole is an opening drilled into the side of a barrel and is used to fill the cask with spirits, beer, cider, soda – or anything else we may want to barrel age.

This is one of the final steps in coopering. But planning for the bunghole takes place early in the process. When Nate assembles the staves, he includes two extra wide pieces to use as bung staves. He’ll drill a hole in one of the bung staves and has the other piece as a back up.

But a freshly cut bunghole isn’t watertight. Nate’s going to seal it by burning the wood inside the hole.

And for that, he uses a specialized piece of gear called the bunghole cauterizer.

With the bunghole drilled and sealed, we’ve finally got an honest-to-goodness Rolling Thunder Barrel.

Nate has yet to sand the sides, put on new hoops, then brand the barrel with a serial number, information about the toast and char levels, and the Rolling Thunder logo. But those steps are about making it pretty, not functional.